Photographer and poet, Humberto Gatica, talks to Marie Gillespie in a wonderful and inspiring interview where we describes how his life experiences as an orphan, a refugee, an artist and a poet inspire his works and his philosophy of everyday life.

Humberto Gatica was born and educated in Chile. He came to UK as refugee from the Chilean dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, where he was in prison for nine months. He has published two books of poetry: “Ring y Otros Poemas” (1980) and “The Sand Garden” (Hafan Book 2008). His poetry has been published in print and digital magazines in Europe and the Americas and also in anthologies including: “Another Country” Haiku Poetry from Wales. Ventana Latina 3rd Anthology, and Barbed Wire Blossoms. (The Museum of Haiku Literature Award Anthology1992-2011). His images have been selected for exhibitions, books and magazines. He contributed to “Refuge and Renewal: Migration and British Art, in the Royal West Academy England, (December 2019- March 2020) and MOMA Machynlleth (March –June 2020). He lives in Swansea with his wife Gabriela.

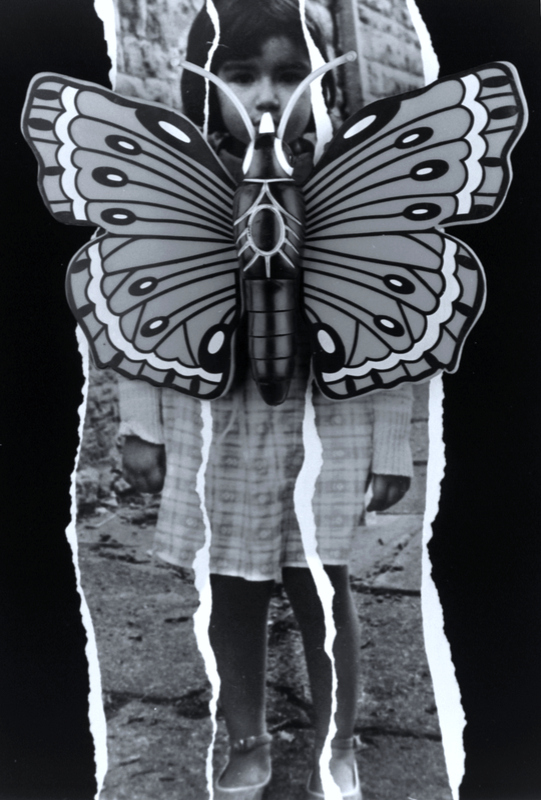

M: The two images you have chosen to exhibit on our Covid Chronicles site are very powerful and compelling. They invite you in, open up questions and urge a response. They also work very well together as a pair. So perhaps we could start with Learning to be a Butterfly – I wondered if you could say a few words about the image and what inspired you?

H: Yes, the two images could be a diptych because they worked very well together then – at the time they were taken – and now, during the pandemic. The symbol of the butterfly, at least from the point of view of Christianity, is one of resurrection, but across cultures it is a symbol of resilience, change and hope. And this is what’s happening, and this is what is needed during this pandemic – so that is why I chose this image.

The symbol of the butterfly … is a symbol of resilience, change and hope… this is what is needed during this pandemic.

Also, for me, childhood is a very difficult time in your life. As you are growing up, you’re taking in everything from your parents, your environment and this very much links to now, to our experience of being at home a lot as well in lockdown. I am thinking about what is home for children from minority or refugee backgrounds or those who have been refugees themselves or are children of the refugee people? They have these two environments in which they grow. But the home environment is a different culture for them to the school or playground culture. The experience is a bit hard. It can be a bit difficult to deal with life. Not always. But they have limited options, no power, no control and that is what life is like in this pandemic too- as well as for some asylum seekers. But children have to change. They need to grow. We also need to change and grow after this pandemic experience. We need to rewire our perception about what reality is, what this new reality means and learn to find hope. When I was working on that image that’s what I was thinking because it conveys a sense of hope – it is essentially an image hope.

Children… have limited options, no power, no control and that is what life is like in this pandemic too as well as for some asylum-seekers. But children have to change. They need to grow. We all need to change and grow after this pandemic experience.

The time we’re living in now we need a lot of hope because nobody knows what is going to happen next. Even the scientists do not know, and their approach is more or less one of trial and error and that is what we are doing and what we, as a human beings, need no – to play a role as well and to hope, and look at how we are going to manage and how we’re going to survive. People are dying.

When you wake up in the morning and realise that you’re still alive, now you feel this is a kind of lesson. It is a kind of gift. It gives us hope.

We live in a very toxic environment – politics, media and misinformation can be toxic, so we have to escape from them because if not, we are going to get very confused because there’s a lot of confusion now.

Everyone tries to preach their own point of view, but people must find their own truth and their own way. Both the butterfly and the child will have to grow and find their own way.

They will have to find their own truth.

This is essential when you’re growing up between two cultures. It is a little bit more complicated for them because they have more choice, but some children reject the culture of they have at home. They don’t want to speak their home language, or they’re not interested in the tradition. Or they reject their parent’s faith and you see. And when I think of the pandemic and I think:

how will children from migrant backgrounds grow and change and find their own pathway – how are they going to the recover from that isolation at home with parents and with such little contact with friends or school.

They have missed so much. Psychologically, it’s difficult to say what will be the impact will be. What the effect of no touch – no physical contact will be. But this pandemic is in every country around the world and in the all those places it is the same story. It’s a collective trauma. It is. It has become normal. It is very much in the air. You can breathe in the reactions of the people,

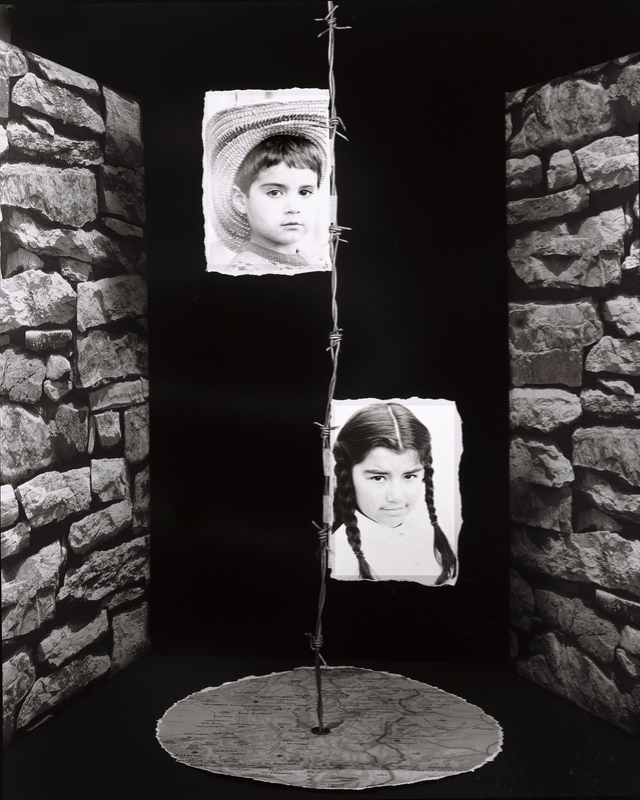

M: Thank you Humberto – and A Tale from Now?

Well, this is the the other side of the coin now. The image was designed to explore the period or the moment in which a child is growing up – it explores a philosophy of everyday life and asks:

What if a child has not had the opportunity to discover things? What if all the things shaping their perceptions are painful?

In any case growing up and all associated processes are usually painful. They were for me. I was an orphan and the image is very much related to my own experience. I grew up in care. I was raised by my uncle. A Tale from Now is a very personal perception. The photos are of my son and my daughter. I was trying to show the tendency in life for a child to explode into drama, but at the same time I was very much interested in the subtle beauty of that drama. The image could maybe serve as a kind of contradiction. That is the way I perceive it because I always say:

when you have a bad experience, when something wrong happens, if you make a mistake – this is telling you something. With that bad experience, you have the chance to make a new start. This is my philosophy of everyday life – maybe a refugees’ philosophy.

The pandemic helped me expand my time and that was good for me because when I work or when I am invited to produce work, I need time to think through it very well. And I need to explore options- the pandemic gave me time to think through a lot of different options. The barbed wire is a symbol of pain. Then I try to define a vision, a particular kind of experience with a particular kind of situation? The two images there now appear like flags. That is the way the children are concerned essentially with their family and friends who are very important to them. But conflicts arise with their environment with their family and friends and this may prevent them from growing and changing and finding their own pathway. We need to understand or to guide them to build their own personality, because sooner or later they have to leave home and know how to be in an open environment, and they need to be ready to deal with that. Sometimes even me I can become a little bit confused by what meanings lie under the images I create. I produce images and have an image in my mind, but when halfway through, I start asking, what that means, why even doing this?

M: Well it’s a very intriguing image. I see the two children as you say – like as flags, but there they are a knife edge of pain or suffering. And then that’s surrounded by walls.

H: The walls are the limitations you have as children as they do not have very much voice – everyone is telling you do this, is always telling you do that – what you need to do or what you must do. Sometimes even the children don’t understand why they are being told to do things. There is no way for them to understand. They just have to follow orders. I guess we too have had to follow orders in this pandemic.

M: It looks like there’s a map. Is it a map?

H: Yes, yes. This is a map of Chile – my home country. I try to look for the best way of representing these kinds of experiences. My own childhood was very isolated, in a very small village – a little bit difficult and there is a lot of social pressure as well.

Generally speaking, orphans are not welcome anywhere, like refugees.

In recent decades we have seen the ways orphans are treated and how living in orphanages is like living in prison – look at the news reports from Romania. Bulgaria and some other country of the Eastern Bloc. But it is same in Latin America is even here in Europe today children in care can be treated very badly. My experience of childhood is therefore a little bit different from the normal childhood and has shaped me. So, I don’t know, but in the end the images are my experiences and I also express these experiences in poetry.

M: Thank you for a fascinating conversation and next time, I’d love to read and then talk about your poetry – next time – hopefully

7 May 2021

If you have enjoyed reading this blog post please share by clicking the buttons below. Sharing will also help us get our message to more people.